Two Writers Walk into an Elevator

Paulette Perhach | February 2020

I didn’t decide to go to AWP with my poet friend Michelle until my FOMO spiked just a few weeks out, and by then the hotels were booked. This was the LA year. Our budget for four people (our partners tagged along) suggested an Airbnb. We settled for a 2-bedroom white cubic sample of the same sort of blandification that keeps rising on the graves of craftsman and brick masterpieces in Seattle, an affliction you probably understand if there’s a city you love. The building, called TENTEN Wilshire, was, according to its website, “A New Lifestyle Solution for Professionals.” It wasn’t until we saw the red light of a LIVE 1010 LED sign bathing the entire intersection, as well as a huge on-site Buddha statue, that we realized what we’d done.

In the lobby, behind the espresso machine and massage chairs, a security desk with a grid of screens monitored empty hallways and a still pool on the rooftop deck. Dirt caked the corners of the hallway among a scatter of stubbed-out cigarettes. By the time we reached our floor, the building seemed best suited as a solution for corporate travel and porn shoots. Signs in the elevators reminded us that we needed permission to film.

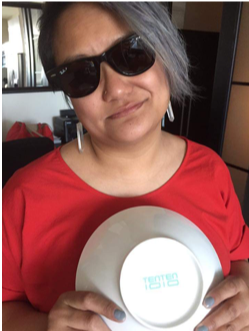

In the apartment, we found TENTEN branded everything. TENTEN printed on every mug and plate. TENTEN on the blinds. TENTEN imprinted in the bathroom rug, so you could feel it under your naked feet.

“Wow you’re really TENTEN-ing right now,” I’d say to Michelle, as she lay on the couch with the sunlight from the inarguably enjoyable floor-to-ceiling windows glinting in the sunglasses she’d found (also emblazoned with the logo for the building.)

“TENTEN for life,” she’d respond.

The coffee shop downstairs did deliver caffeine and breakfast sandwiches directly to our hangovers in the mornings, so I can’t complain about that. Amenities are nice. But amenities are just sprinkles. They are not the thing itself.

During the days, after 7 years of considering myself a creative writer, I finally found out what it was like to arrive at the largest collection of people considering themselves the same, at AWP.

I didn’t know what to expect. I decided to let it just wash over me, no expectations. I hefted that same anxiety most of us feel around thousands of people doing the same thing we want to be doing, luminaries doing it much, much better than we’re able to do it just yet, so I wandered into events and tried to sit in a back corner, steadied by my shoulder against a wall.

What I heard helped me forget my squeaking ego, or anything outside the room, the moment. Whereas the architectural world around me is narrowing toward sameness, at readings I felt a renewed delight at the structures words can craft in my mind, the nameless emotions they can bloom in my chest. Tyehimba Jess’s kaleidoscopic poems raising the lid on what I thought form could be. Lidia Yuknavitch’s version of womanhood that asks me why I hide so much of myself. Natalie Diaz’s soft voice, slicing the skin off my perspective, exposing new layers that see the old anew. The work, the existence of all these people who, like me, dedicate their life to this craft, swelled me with all that lets me know I’m human.

On the second to last day, Michelle and I went upstairs to try to make up for living in Seattle by catching the last horizontal beams of the sun before the evening readings. Sharing a round chaise longue, watching a male model sashaying back and forth along the water’s edge, caressing both sides of his head as he walked, we were definitely TENTENing.

But before we could even warm, some dude came over and politely asked us if we could clear out. They had a fashion show to set up for, because of course they did.

In just our swimsuits, towels, and flip-flops, we got in the rooftop elevator, which someone on Yelp would later describe as “super rocky and TINY.”

Just as the doors were closing, we saw our partners, who had come upstairs looking for us. I hit the Door Open button, right as it closed. It did not open. We hit our floor button. It did not descend.

We tried both again. Nothing.

We tap tap tap tap tap tap tapped. Stillness.

We looked at each other. I turned to the eye of the security camera in the corner, mouthed “Help!”

Our partners left, with us trying to yell after them.

For the first time in my life, I got to push that red “in case of emergency” button. So at least there was that.

The thing about being stuck in an elevator is that you don’t know how long you’ll be there. And you don’t know how much air you breathe per breath, and how much is in there, or if any is getting in, and you never should have watched that Lifetime movie when you were a kid about the girl who got buried in the box designed by the psychopath, where she could either have the light on and breathe longer, or turn it off and use the fan to get more oxygen.

I started to feel it in my throat, that feeling that makes me a person who has zipped herself into a mummy sleeping bag exactly one time, for exactly one second.

“I’m getting claustrophobic,” I said.

“No, you’re not,” said Michelle, using her Jedi mind trick. She talked me down.

Finally, humans came. They asked if we were stuck.

“Yep!”

We gave in to our condition, sat on the dirty tiled floor. We stood. The temperature rose. I pressed my cheek against the metal wall, gripped the cool handrail. We sat again. We thumbed our phones like mental pacifiers. We heard people talk about us and lament the broken elevator.

If I remember correctly, we started to crack about 20 minutes in. One of us would yell “Gah, cooooooome oooon.”

Sirens sounded in the distance, then less in the distance.

“Are those for us?” I asked. The firefighters arriving answered that question.

More time passed. In the Tetris of our movements, I was sitting against the doors, right in the middle. “You might not want to sit there,” said Michelle. I scooted over. No more than 2 minutes later, a screwdriver pierced through with the force it would take to separate metal doors and, I’m guessing, pierce a lung. So I guess you can say: POETRY SAVES LIVES.

We took photos conceptualizing our feelings, me gripping the crack that had been created by the screwdriver and yanking, Michelle backed against the wall, arms out, mouth open in madness, not knowing how many people were gathered around the front desk, watching us on the security camera. The giggles of mishap took over.

Then I had the idea. I turned from the camera’s eye, balled up my towel, and shoved it down the front of my swimsuit. I sat against the wall again, leaned my back against the dimpled metal, and started having contractions.

“Just breathe,” said Michelle. “You can do it.”

In high school, my friends often said to me, “You’re weird.” They were right, of course. But over my life, I’ve found people, so many of them writers and artists, who catch my weirdness when I lob it their way, sprinkle on another layer, and toss it back. My friend Ryan and I will be walking, and I’ll say, perhaps, that a trash can lid looks like a mouth. “Trash can mouth,” he’ll sing, with his trained stage voice, “talkin’ trash.” Others might have simply left it at, “You’re weird.”

There are 1,000 ways someone could make being stuck elevator a hotbox of hell. Simply complaining the entire time, pounding on the door and promising to contact a manager, or saying, “This is ridiculous,” my favorite terrible phrase, on repeat. I was glad to be stuck in there with another writer, someone with whom it would become a diorama of weirdness, to pass the time.

When the doors finally opened, nearly an hour later, they did so to a nighttime tableau: three firefighters in a bulky crumble of yellow protective fabric and helmets in the foreground, backed by a chorus of models in clubwear, smiling their made-up faces, applauding with their delicate hands like we had just completed a piece of performance art. The firefighters made way, revealing our sweat and flesh and towel skirts and toes to the crowd.

“Thank you,” we muttered, heads down, flip flopping out of there under the multicolored lights.

A writer’s life is near-terrible, we all agree. From my social media research, it seems we all wonder what we’re doing, if it’s worth it, if we should be somewhere else. No one hands this to us, says, “This is what will make you happy.” No one sells us this life. We all had to create this, our own way of being a writer. We had to decide that this was what we were going to do. We did not just accept some default mode of living, did not seek this as an easy lifestyle solution. If anything, it’s a lifestyle problem we will spend the rest of our lives trying to solve, and it helps to be with one another, to experience the kind of moments that remind us of what is possible.

On the final day that time in LA, I was talking with a woman who seemed stricken by real, last-day-of-camp grief. “I don’t want to go home,” she said, brow furrowed as if from worry. “I don’t have anything like this where I’m from. I don’t know any writers.”

Even though I’m lucky enough to know writers where I live, and even though I should throw the money for flights, food, and better lodging toward my credit card bill, and even though I refuse to get in an elevator with Michelle Peñaloza, I have yet to skip a year since my first in that temporal world I so prefer. One weekend a year, this is where I live.

Paulette Perhach is an author and writing coach who offers AWP prep checklists and other resources you can get by signing up via Mailchimp. Her work has been in the New York Times, Hobart, Elle, Vice, Marie Claire, Yoga Journal, and McSweeney's Internet Tendency. She's the author of Welcome to the Writer's Life, selected as one of Poets & Writers' Best Books for Writers. Her work has been anthologized in The Future Is Feminist from Chronicle Books, along with work by Roxane Gay, Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie, Caitlin Moran, and Audre Lorde. She writes about all writers need to thrive—craft, business, personal finance, and joy—at WelcomeToTheWritersLife.com.